Guest Editorial by Jo Ritchie

Environmental News Issue 10

I owe a lot to Great Barrier. In my past life as a naïve D.o.C recreation planner I spent two summers on the island running the summer holiday programme. I had a great teacher in Don Woodcock and through his knowledge and experience I was able to take people for great walks and experiences across the island. I learned quickly that this is a place of great contrast — the most memorable one being told that the weather was wonderful in summer only to come out and have three cyclones in six weeks and spend New Years Eve getting revelers out of their tents at Kaiarara Bay as the creek burst its banks.

It’s nice now to be able to come and give something back to a place that taught me a lot about island life, the complexities of integrating people and conservation and the passion that people have for the place they live in.

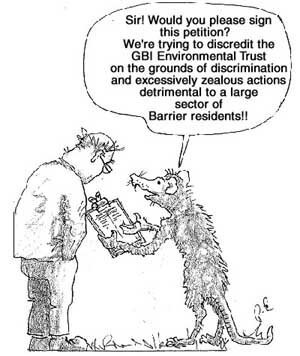

The Great Barrier Island Charitable Trust has had a bit of a rocky ride. I can appreciate both sides of the debate in the community—wanting to remove animal pests from the island and the concerns about wide scale use of some control techniques such as toxins in the environment. However the bottom line is that Great Barrier is a special and unique place. A lot of this is to do with the unwavering dedication of the people who live there to keep it a special place, but it also has a lot to do with its wilderness qualities and the fact that key animal pests which are wreaking such havoc on the mainland such as possums and mustelids are not on the island.

It’s significantly important that an island the size of Great Barrier so close to Auckland, with minimal biosecurity measures and so accessible to visitors, has so few species of animal pests. However what this means is that the few that are present can take maximum advantage of their environment—a well-stocked larder in the forests, wetlands and farmland and superior housing with low competition from other predators.

Some would argue that minimal bio-security can work — look at Motuora Island, which has never had rodents but is easily accessible to the public who can land boats on the beach. However this is an anomaly and is more good luck than planning. Biosecurity measures need not be disruptive to people’s lives. It’s more about valuing the uniqueness of a place and taking simple steps to ensure new pests do not establish. Boats are probably the greatest source of a new pest — rats are commonly known to stowaway on boats. This is a common cause of reinvasion onto offshore islands where eradications have been undertaken. Simply checking your boat on a regular basis and periodically setting and maintaining a bait station or trap is all that is need-ed. In practice all other biosecurity measures are this simple.

Animal pests in whatever form are NOT a part of our natural environment in New Zealand. Unlike other environments (e.g. Australia) our native species did not evolve with the ability to defend themselves against predators and competitors. As a result New Zealand has experienced one of the highest extinction rates of native species in the world.

The sad thing is that with all our knowledge today this trend continues. Many native species only thrive on offshore islands where eradication programmes have been undertaken and where it is difficult for people to visit. On the mainland keystone species such as kiwi and kereru are in rapid decline. And its not only the birds that suffer — unfortunately most animal pests eat anything that walks, crawls, flies or grows and so the basic life support systems of many of our ecosystems — invertebrates and vegetation are constantly under pressure. To make matters worse it’s not as simple as saying well lets remove the rats and everything will be fine. The problem is like most things in life — everything is connected to everything else – take out one component and another problem occurs — remove rats and then cats will increase their consumption of another food source (most likely native) to compensate.

But there is hope and it involves a simple equation — integrating people and conservation. A lot of my work is in working with communities and groups to reverse the effects of animal pests, restore natural environments and minimize impacts on surrounding landowners. There is invariably compromise and to be effective it has to be on both sides. For me effective communication is listening to and respecting ALL sides regardless of whether I agree or not and then trying to work out some form of action plan that meets everyone’s concerns — for me problems are challenges to overcome. This may seem overly simplistic or a bit dreamy but it does work and it works well. Honesty and openness is also important — I have found that a lot of the issue around various pest control measures is a result of people being provided with limited information. Every pest control measure has advantages and risks and all need to be presented openly so people can make well-informed decisions about their use and impact.

However, at the end of the day it’s people that make the difference. I would like to see more debate and innovation on how we could improve the lot for native species and natural environments on Great Barrier.

I would like to see the development of a community-led strategy for improved integrated management of all of the natural environments on the island — be they D.o.C, iwi, private or community trusts. Concerns about who pays and what effects it has on personal freedom and pockets do need to be addressed but I would argue that if such a strategy were developed that had the support of the whole community, funding sources would not be hard to find and the outcomes would be beneficial for both the local community and the environment.

Jo Ritchie works as an environmental planner and project manager, principally in the areas of restoration ecology and animal pest eradication. She has worked in the Auckland Region for nearly 20 years, this included 12 years working for D.o.C as a recreation planner and field officer. For the last 7 years she has run her own business and worked on projects such as the Tawharanui Open Sanctuary, a number of pest fencing projects around the country, prepared several restoration plans and worked with a wide range of community groups. Her emphasis is on practical conservation – the out there doing part and involving the community as much as possible.